I arrived in in Paris with a plan in my mind: to make a pot-au-feu recipe from a nineteenth-century French cookbook. It was for a book project that had begun to bubble and form in my mind, about national food cultures told through their symbolic dishes and meals, which I would cook, eat, and investigate in different parts of the world.

Now I sat on a Parisian park bench in the multicultural 13th arondissement—unwrapping a hyper-globalized sushiburrito while I contemplated a super-essentialist quote from the great scholar Pascal Ory. France, wrote Ory, “is not a country with an ordinary relation to food. In the national vulgate food is one of the distinctive ingredients, if not the distinctive ingredient, of French identity.”

Italians, Koreans, even Abkhazians would certainly wax indignant that their relation to food is every bit as special. But if our identities, at their most primal, involve how we talk about ourselves around a dinner table, it was France—and Paris specifically—that created the first explicitly national discourse about food, esteeming its cuisine as an exportable, uniquely French cultural product along with terms such as “chef” and “gastronomy.”

It was France that in the mid-seventeenth century laid the foundation as well for a truly modern cuisine, one that emerged from a jumble of medieval spices to invent and record sauces and techniques the world still utilizes today. To create “restaurants” as we know them, and turn “terroir” into a powerful national marketing tool.

Stock was homey yet at the same time existentially Cartesian: I make bouillon, therefore I cook à la française.Of course (to my not-so-secret glee, I admit) this Gallic culinary exceptionalism had taken a terrific beating over the past couple decades. So where was it now? And where, and how, did the idea of France as a “culinary country” come to be born?

*

The pot-au-feu that was to occupy me in Paris, my symbolic French national meal, came from a book by a deeply influential nineteenth-century chef whose fantastical story befits an epic novel. Abandoned on a Parisian street by his destitute father during Robespierre’s terror, Marie-Antoine Carême would have been invented—by Balzac? Dumas père? both were gourmandizing fans—if he didn’t already exist.

Self-made and charismatic, he rose to become the world’s first international celebrity toque (in fact he invented the headgear). Not only was Carême the grand maestro of la grande cuisine’s architectural spun-sugar spectaculars, he also codified the four mother sauces from which flowed the infinite “petites sauces,” sauce being so essential to the French self-definition. And cheffing for royalty and the G7 set of his day, he spread the supremacy of Gallic cuisine across the globe. Or to put a modern spin on it, Carême conducted gastrodiplomacy (our au courant term for the political soft power of food) on behalf of Brand France.

Even more influential was Carême’s written chauvinism. “Oh France, my beautiful homeland,” he apostrophized in his 1833 seminal opus, L’Art de la Cuisine Française au Dix-Neuvième Siècle, “you alone unite in your breast the delights of gastronomy.”

How then are national cuisines and food cultures created? The answer, as I’d come to learn, is rarely straightforward, but a seminal cookbook is always a good place to begin. And as the influential scholar of French history Priscilla Ferguson observed, it was Carême’s books that unified La France around its cuisine and food language, at a time when French printed texts had begun making the ancien régime’s aristocratic gastronomy accessible to an eager, more inclusive bourgeois public. “Carême’s French cuisine,” Ferguson writes, “became a key building block in the vast project of constructing a nation out of a divided country.”

As the Chef of Kings addressed his public: “My book is not written for the great houses. Instead…I want that in our beautiful France, every citizen can eat succulent meals.”

And the succulence that kicks off his magnum opus is the pot-au-feu, “pot on the fire.” Broth, beef, and vegetables, soup and main course all in one cauldron, it’s a symbolic bowlful of égalitéfraternité that Carême anointed un plat proprement national, a truly national dish. Pot-au-feu carries a monumental weight in French culture.

Voltaire affiliates it with good manners; Balzac and even Michel Houellebecq, that scabrous provocateur, lovingly invoke its bourgeois comforts; scholars rate it a “mythical center of family gatherings.” Myself, I was particularly intrigued by its liquid component, the stock or bouillon/broth—the aromatic foundation of the entire French sauce and potage edifice.

“Stock,” proclaimed Carême’s successor, Auguste Escoffier, dictator of belle epoque haughty splendor, “is everything in cooking, at least in French cooking.”

Stock was homey yet at the same time existentially Cartesian: I make bouillon, therefore I cook à la française.

*

“Carême…pot-au-feu…such important subjects.” Bénédict Beaugé, the great French gastronomic historian, saluted my project. “And these days, alas, so often ignored.”

In his seventies, his nobly benevolent face ghostly pale under thinning white hair, Bénédict radiated a deep, humble humanity—the opposite of a blustery French intellectual. His book-lined apartment lay fairly near the Eiffel Tower, in Paris’s west. Walking up his bland street, Rue de Lourmel, I noted a Middle Eastern self-service, a Japanese spot, and a wannabe hipster bar called Plan B.

“Ah, the new global Paris,” I remarked, to open our conversation.

“And a chaos, culinarily speaking,” Bénédict said. “A confusion— reflecting a larger one about our identity—lasting now for almost two decades… Though a constructive chaos, perhaps?”

He wondered, however, as I’d been wondering, about the “overarching idea of Frenchness, of a great civilization at table.” In Paris nowadays, he said, only Japanese chefs seemed fascinated with Frenchness, while Tunisian bakers were winning the Best Baguette competitions.

“Yes, immigrant cuisines are changing Paris for the good,” he affirmed. “But the problem? In France, we don’t have your American clarity about being a melting-pot nation.”

Indeed. Asking journalist friends about the ethnic composition of Paris, I’d been sternly reminded that French law prohibits official data on ethnicity, race, or religion—effectively rendering immigrant communities like the ones in our treizième mute and invisible. All in the name of republican ideals of color-blind universalism.

“Ah, but pot-au-feu!” Bénédict nodded approvingly. “That wonderful, curious thing, a dish entirely archetypal—meat in broth!—and yet totally national!”

As for Carême? He smiled tenderly as if talking about a beloved old uncle. “An artiste, our kitchen’s first intellectual, a Cartesian spirit who gave French cuisine its logical foundation, a grammar. However…” A finger was raised. “The rationalization and ensuing nationalization of French cuisine—it didn’t exactly begin with Carême!”

“Ah, you mean La Varenne,” I replied.

In 1651, François Pierre de La Varenne, a “squire of cooking” to the Burgundian Marquis d’Uxelles, published his Le Cuisinier François, the first original cookbook in France after almost a century dominated by adaptations of Italian Renaissance texts—and the first anywhere to use a national title.

Hard to imagine, but until the 1650s there really wasn’t anything remotely like distinct, codified “national” cooking, anywhere. While the poor subsisted on gruels and weeds (so undesirable then but now celebrated as “heritage”), the cosmopolitan cuisine of different courts brought in delectables from afar to show off power and wealth.

All across Europe, cookbooks were shamelessly plagiarized, so that European (even Islamic) elites banqueted on pretty much the same roasted peacocks and herons, mammoth pies (sometimes containing live rabbits), and omnipresent blancmanges, those Islamic-influenced sludges of rice, chicken, and almond milk. Teethdestroying Renaissance recipes often added two pounds of sugar for one pound of meat, while overloads of imported cinnamon, cloves, pepper, and saffron made everything taste, one historian quips, like bad Indian food.

Le Cuisinier François offers the earliest record of a seismic change in European cuisine. Seasonings in La Varenne’s tome mostly ditch heavy East India spices for such aromates français as shallots and herbs; sugar is banished to meal’s end; smooth emulsified-butter-based sauces begin to replace the chunky sweet-sour medieval concoctions.

Le Cuisinier brims with dainty ragouts, light salads, and such recognizable French standards as boeuf à la mode. One of La Varenne’s contemporaries best summed up this new goût naturel: “A cabbage soup should taste entirely of cabbage, a leek soup entirely of leeks.”

A modern mantra, first heard in mid-seventeenth-century France. “Then following La Varenne, in the next century,” said Bénédict, a frail eminence among his great piles of books, “the Enlightenment spirit fully took over, while print culture exploded.” Fervent new scientific approaches teamed up with Rousseau’s cult of nature, whose rusticity was in fact very refined and expensive. Among other things, this alliance produced a vogue for super-condensed quasi-medicinal broths.

And the name of these Enlightenment elixirs? Restaurants.

As historian Rebecca Spang writes in The Invention of the Restaurant, “centuries before a restaurant was a place to eat…a restaurant was a thing to eat, a restorative broth.” Restaurants as places—as attractions that would be exclusive to Paris well into the mid-nineteenth century—first appeared a couple of decades before the 1789 Revolution, in the form of chichi bouillon spas, where for the first time in Western history, diners could show up at any time of day, sit at their separate tables, and order from a menu with prices.

By the 1820s Paris had around three thousand restaurants, and they already resembled our own. Temples of aestheticized gluttony, yes—of truffled poulet Marengo and chandeliered opulence. But also, crucially, social and cultural landmarks that inspired an innovative and singularly French genre of literary gastrophilosophizing—attracting Brit and American pilgrims who assumed, per Spang, that France’s “national character revealed itself in such dining rooms.” Which it did.

“Of course national cuisines don’t happen overnight,” cautioned Bénédict, as I made ready to leave him to his texts and histories. It was a long process that mirrored developments in culture and politics. But one uniquely French hallmark, he stressed, going back to the mid-1600s, was a culinary quest for originality and novelty, made even more insistent by the advent of restaurants and the birth of the food critic.

And pretty much ever since La Varenne, each triumphant new generation of French cuisiniers has expressed a recommitment to the ideal of goût naturel, to a more inventive and scientific—and more expensive—refinement. Carême? He, too, professed the “vast superiority” of his cuisine on account of its “simplicity, elegance… sumptuousness.” Escoffier boasted of simplifying Carême—to be followed by an early-twentieth-century cuisinebourgeoise regionalist movement that ridiculed Escoffier’s pompous complexities. Then the 1970s nouvelle cuisine rebels (Bocuse, Troisgros, and the like) attacked the whole Carême-Escoffier legacy of “terrible brown sauces and white sauces” to raise the conquering flag of their own (shockingly expensive) lightness and naturalness.

*

I spent my next weeks in Paris literally knee-deep in bouillon, researching pot-au-feu along with the history and science of stocks—fishing for broader connections between cuisine and country. It amazed me, for instance, how an eighteenth-century cup of restorative broth sat so smack at the French Enlightenment’s intersection of cuisine, medicine, chemistry, emerging consumerism, and debates about taste, ancienne versus nouvelle.

While a century later, broth represented democratization of dining, as inexpensive canteens called bouillons—the world’s proto–fast-food chains—sprang up in fin de siècle Paris, serving beef in broth plus a few simple items to disparate classes in hygienic, gaily attractive surroundings.

Now in the living room of our apartment rental with its clutter of Balzacian bric-a-brac, I reexamined once again Carême’s opening recipe in L’Art de la Cuisine Française: “pot-au-feu maison.”

Put in an earthenware marmite four pounds of beef, a good shank of veal, a chicken half-roasted on a spit, and three liters of water. Later add two carrots, a turnip, leeks, and a clove stuck into an onion . . .

A straightforward recipe, if a little weird. Why the half-roasted chicken?

The more I thought about it, the more pot-au-feu seemed like an obvious master class in “national dish” building.What made the recipe a landmark, Bénédict told me, was Carême’s Analyse du pot-au-feu bourgeois, his opening preamble. For here was the Chef of Kings, who’d dedicated his pages to Baroness Rothschild, explaining the science and merits of bouillon for a bourgeois female cook—bridging the gap between genders and classes, praising his reader as “the woman who looks after the nutritional pot, and without the slightest notion of chemistry… has simply learned from her mother how to care for the pot-au-feu.” This preamble, according to scholars, was what truly nationalized the dish, leading generations of writers and cooks to start their own books with this one-pot essential.

But how else, I asked myself, and for what other reasons, do dishes get anointed as “national”?

There was unexpected economic success abroad (pizza in Italy); tourist appeal (moussaka in Greece); nourishing of the masses during hard times (ramen in postwar Japan). Even, sometimes, top-down fiat: see the strange case of pad Thai, a Chinese-origin noodle dish (like ramen) that got “Thaified” with tamarind and palm sugar and decreed the national street food by the 1930s dictator Phibun—part of his campaign that included renaming Siam as Thailand, banning minority languages, and pushing Chinese vendors off the streets.

Among all the contenders, of course, one-pot multi-ingredient stews made the most convincing national emblems with their miraculous symbolic power to feed rich and poor, transcend regional boundaries, unite historical pasts. In Brazil, feijoada was canonized for supposedly melding Indigenous, colonial, and African slave cultures in a cauldron of black beans and porkstuffs, while in Cuba the exact same thing was said about the multi-meat tuber stew, ajiaco. Or consider (if one must) the creepy Nazi promotion of Germany’s eintopf (“one-pot”) for forging some mythical völkisch community. Never mind that the word “eintopf” never even appeared in print until the 1930s. (A not-uncommon sort of situation, I would discover.)

And so here was my pot-au-feu with its very genuine historical roots. Although hardly a dish of the peasants (for whom meat was once a year) it was still easily mythologized as the perfect embodiment of French republican credos, a fraternal pot for toute la France. Even that towering snob Escoffier praised it as a “dish that despite its simplicity…comprises the entire dinner of the soldier and the laborer…the rich and the artisan.”

By Escoffier’s belle epoque reign, France’s Third Republic ambition to aggressively nationalize its citizenry through universal education, military service, regional integration, and rural modernization was almost fulfilled. Although women remained second-class citizens—unable to vote until 1944—“teaching Marianne how to cook,” as one scholar puts it, “had become a national issue of paramount importance.”

And pretty much every domestic science textbook for girls began with pot-au-feu, which was also the name of a popular late-nineteenth-century domestic advice magazine for bourgeois housewives. Why, pot-au-feu even perfectly illustrated the era’s embrace of regionalist “unity in diversity,” since every region in France had its version (garbure in Languedoc, kig ha farz in Brittany), all now celebrated as parts of a grand, savory national whole.

The more I thought about it, the more pot-au-feu seemed like an obvious master class in “national dish” building.

__________________________________

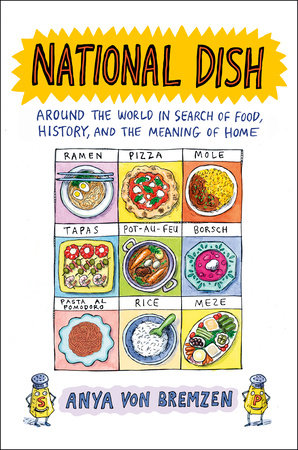

Adapted from National Dish: Around the World in Search of Food, History, and the Meaning of Home by Anya von Bremzen. Copyright © 2023. Available from Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.